Articles/Opinion » Sikh News » Special News

Bapu Chaman Lal, Who Lived for a Hundred Years But Died Waiting for Justice

July 7, 2016 | By MALLIKA KAUR

Author: MALLIKA KAUR

For a turban-wearing, Urdu-reading Hindu of Taran Taran, Punjab, the court’s recess was 23 years too long. On June 30, 100-year-old Chaman Lal breathed his last, two days before the case he had been pursuing for over two decades was to resume in the CBI court, Patiala.

On April 25, the Supreme Court of India passed a much-awaited essential order: it lifted the previously imposed “stay” on the trial of 37 criminal petitions related to Punjab’s mass clandestine cremations, first revealed in 1995.

“See, I said I wouldn’t die without seeing this through…this is the 32nd member of my family lost to senseless violence. And this one’s life had just started. And this one’s life was taken by those meant to protect him,” Lal said last month, shivering a little even in the sweltering heat, as we spoke about the season’s first jamuns.

“Another summer, we are closer to his death anniversary…” he trails for a minute before the map of wrinkles on his face once again guides us through his long ache and persistent advocacy.

Lal’s son, Gulshan Kumar, was 20 years old when he was abducted from his home on June 22, 1993.

Home had once before been ripped apart entirely, in front of Lal’s young eyes.

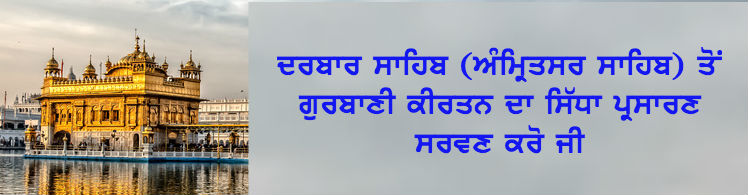

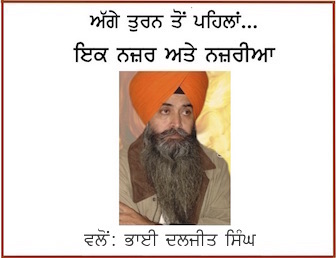

![Bapu Chaman Lal (Center) [File Photo]](https://sikhsiyasat.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Bapu-Chaman-Lal-Center.png)

Bapu Chaman Lal (Center) [File Photo]

Ripe jamuns stain everything they touch, starting with the ground they hit. The fruit of the Syzygium cumini tree has an acidic taste. As summer peaks, evergreen jamun trees become laden with the deep purple oblong berry and roadside vendors appear with their pyramids of jamuns, salted to counter the tannins. The tongue turns a volitional purple and the mouth dries. Breathing in through the teeth, feeling the cool astringency against the blistering heat, renders the fruit worthwhile again.

In 1947, by the time the jamun trees were in full bloom in the early summer, the entire landscape of Punjab was being coloured forever.

“I was 32-years old during the batwaraa (partition).”

Punjabi grandparents speak of this celebrated national high holiday only as the year of batwaraa, when everything was shredded in a span of weeks, forever. As east and west lost two-and-a-half of their rivers, they together lost at least half a million lives. Thirty-one of these were Lal’s family members in Lahore.

He received a small plot of city land in lieu of the family’s agrarian fields left behind in now Pakistan. He built a small house in the city of Taran Taran.

In 1993, through the tight lanes outside his one-room house, Gulshan would wheel a vegetable cart. Lal ran a small shop selling cloth; Gulshan had six younger siblings.

As he would call out to customers, hawking vegetables home to home, Gulshan came to witness a local man often harassing young girls on their way to school.

“This was some Balwant Singh, a lawyer. Gulshan told him to stop one day. And he was furious, he threatened that the DSP [deputy superintendent of police] is a friend, a classmate of his, and he could have Gulshan put away forever in a terrorism case.”

This was a dangerous threat in 1993.

The year’s litany of cases had opened with the notorious case of the ‘disappearance’ of Kulwant Singh, a human rights lawyer, along with his wife and two-year-old child; just on the heels of the ‘disappearance’ from custody of the jathedar (leader) of the Akal Takht in Amritsar, Gurdev Singh Kaonke. (Both cases were later investigated as murders in police custody.)

Lal’s family was by comparison politically insignificant, but thus also increasingly vulnerable. They had, however, shaken off Gulshan’s run-in and instead prepared for his nuptials, just two months away.

Three nights before the wedding, the local DSP brought a team to Lal’s house. All the male members were beaten in the eight-by-ten-foot verandah where they had been asleep. Gulshan was especially targeted. As neighbours gathered, the police loudly declared they were searching for stolen goods.

“Did they find something? No stolen goods of course! But they stole three of our gold rings, one watch, and Rs 475 kept aside for the sabzi mandi(vegetable market),” Lal said.

Lal and his sons were taken to the police station, while neighbours intervened to stop the police from also taking Lal’s daughter, Inderjit.

“We were out in a few days, after harsh beatings, but they said to bring Rs 2 lakh if we wanted Gulshan back. And we had seen what happened in there… ”

From June 22 to July 22, Lal kept visiting the jail and watched his son deteriorate; the boy was soon unable to eat solids. Then one day, a policeman sitting outside told Lal to not enter the jail, but go look for his son at the hospital.

“I saw four dead bodies there, bruised and now bullet-ridden. The policemen saw me and pushed me away… They were the judges, they were the executioners, they believed themselves all powerful.”

The impunity in Punjab’s countryside would be proven widely a year later. The rumouring winds in conflicted Punjab had carried Jaswant Singh Khalra and his colleagues to crematoria where police were bringing bodies and having them burnt as “unclaimed”. Khalra and his team discovered municipal records, kept to account for the firewood used for the surreptitious burning. Their very first press note in January 1994 noted 400 such bodies brought to the Patti and 700 to the Taran Taran cremation grounds.

Khalra’s demand that the Punjab mass cremations case be entrusted to the CBI was fulfilled around two months after his own disappearance from right outside his Amritsar residence, on September 6, 1995. Two months later, on November 15, the Supreme Court ordered the CBI to take charge of both the investigation into Khalra’s disappearance from his doorstep and into the facts alleged in by the team’s sensational press note:

It is horrifying to visualize that dead-bodies of large number of persons – allegedly thousands, could be cremated by the police unceremoniously with a label “unidentified.” Our faith in democracy and the rule of law assures us that nothing of the type can ever happen in this country but the allegations in the Press-note – horrendous as they are – need thorough investigation.

In the mass cremations case, a CBI interim report confirmed 984 illegal cremations in the Taran Taran district between 1984-1994. “Kidnapping of a person whose family is totally in [the] dark about his whereabouts – even about the fact whether he is alive or dead – is the worst crime against humanity,” the Supreme Court thundered.

Gulshan had been on the Taran Taran list of those cremated in secret. But there was an eyewitness: Lal.

“When reading the Urdu newspaper one day…that’s the only paper I can read…that there were human rights folks speaking out about secret cremations, I read that Justice Ajit Singh Bains was encouraging families to come forward…I ran to Amritsar for this meeting.

“See, after I was beaten away from the hospital on July 22, 1993, I had gone to the cremation ground…sachh khand. They yelled, ‘You reached here too?’ But they were busy. I watched and wailed. First Gulshan Kumar. Then, Jarnail Singh. On top of him Karnail Singh, then Harjinder Singh…pile of bodies, small pile of wood, rubber tires, and mitti-da-tel (kerosene). That’s it…just like that.”

In 1995, the Supreme Court had directed the CBI to continue criminal investigations related to the mass cremations – though the venerated CBI had attempted to curtail its own mandate repeatedly, asking the court to transfer investigations against the Punjab police back to the Punjab police itself. (“Mr. Sharma has suggested that since a large number of cases may have to be registered, the CBI may be permitted to undertake investigation of 10-15 cases and the remaining cases be investigated by the Punjab Police…..While appreciating the work of CBI, we are of the view that as at present the CBI should undertake investigation of all the cases which are to be registered as a result of the final report,” held in Paramjit Kaur v. State of Punjab 1999 2 SCC 131, by an order dated December 11, 1996.)

In the next few years, the CBI’s investigations would in fact be limited to a handful of cases; Gulshan’s killing was one of the few that was completely probed. Summarising their investigation, the CBI charge sheet of 1999 notes:

That the scrutiny of police file of case FIR No.58/93 showed that there was actually no involvement of Shri Gulshan Kumar except the fact that his name was mentioned as an accused in the case diary dated 16.8.93 written by SI Balbir Singh. Moreover. the said case was registered on 7.7.1993 i.e. the period when Shri Gulshan Kumar was very much in the custody of the PS City Tarn Taran itself.

The charge sheet then notes a planted revolver, false witnesses (“who denied to have ever visited the scene of encounter or ever identified the deceased persons”) and a destroyed DDR (Daily Dairy Record) by the accused police officers.

After this CBI charge sheet put on record that Gulshan was “forcibly abducted” and then killed “in a fake encounter on 22.07.93,” the case didn’t move to a logical conclusion.

On December 12, 1996, the Supreme Court had quoted a final CBI report, which had thus far been confidential, confirming 2,097 illegal cremations of which 585 bodies were fully identified, 274 partially identified and 1,238 unidentified by available documentation. By 2001, the accused had succeeded in having the Supreme Court grant an “interim stay” in the few cases, including Gulshan’s, which had been investigated by the CBI for criminal culpability. The rest remained murdererless murders.

Lal squats down with the flexibility that one who is decades younger can only envy. Around him are strewn papers from a jute bag he carries if he is ever far from home. Who knows when a court might call him? He pulls out a laminated card and strikes his finger on two words: human rights.

“I am a member of the human rights movement in Punjab. I have no fear! Daughter, I have been enticed, beaten, threatened and jailed by police for too long to fear them. Last time was just six months ago that they came to coax me. What matters is I am part of Khalra Mission Organisation. That I have worked with lawyers like Rajvinder Bains, with Justice Bains, who himself went to jail at a grand old age. These are the people of mettle. I have now written a will saying that if I die fighting this, Khalra Mission Organisation will carry it on.

“There was no Sikh terrorism here. There was no Hindu terrorism. This was state terrorism and police and politicians filling personal coffers.”

As he begins to answer what sustained him to fight so long against such odds, he raises his hand for a pause.

“Wait, its not that I had fought. I am fighting. I will keep fighting. I will die fighting.

“Look, those killed in Punjab, are the 25,000 Khalra estimated through his work. Plus one. Khalra. Who were these people killed? Citizens of this country. And who were those people who killed them? I lived through British police. Now, here is our non-white police. What was the role given to them? Killing or protecting? What is their job?”

It was precisely this question that the three-judge bench of the Supreme Court considered again this April, as they decided Devinder Singh & Ors. vs. State of Punjab through CBI, the group of 37 cases including Lal’s, which have languished too long.

In a potently sad statement, the court noted, “The facts are more or less similar in all the cases”.

“Defence of the accused person is that it was a case in discharge of official duty and as the deceased was involved in the terrorist activities and while maintaining law and order the incident has taken place.”

The court then noted several cases that set clear precedence that an accused must show a reasonable nexus between action complained of and discharge of duty to claim immunity from prosecution. The court noted it is indeed no defence when “official status furnishes only the occasion or opportunity for the acts”.

The 37 cases resumed in the CBI court in Patiala on July 2. Traveling from Delhi to strategise with Lal’s Patiala lawyer, the veteran advocate Baljinder Singh Sodhi – who is currently taking this case at no charge – advocate Guneet Kaur reflects on the long arc of promised justice: “It’s understood that there will be motions to delay, attempts to appeal again and not allow this to move forward, but the tenacity of parent petitions like Lal who fought as long as I have been alive, is what must keep us going”.

Lal’s body is no more but his spirit continues to inspire an urgent call for justice no less.

About Author: Mallika Kaur is a lawyer and writer who focuses on gender and minority issues in the US and south Asia. She has a JD from the UC Berkeley School of Law, where she is a lecturer, and MPP from Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

Note: Above article was previously published by The Wire, under title “Chaman Lal, Who Lived for a Hundred Years But Died Waiting for Justice BY Mallika Kaur at source url: http://thewire.in/49212/chaman-lal-punjab-mass-cremations/. Its reproduced as above for the information of readers of the Sikh Siyasat News (SSN).

To Get Sikh Siyasat News Alerts via WhatsApp:

(1) Save Our WhatsApp Number 0091-855-606-7689 to your phone contacts; and

(2) Send us Your Name via WhatsApp. Click Here to Send WhatsApp Message Now.

Sikh Siyasat is on Telegram Now. Subscribe to our Telegram Channel

Related Topics: Bapu Chaman Lal (Tarn Taran), Human Rights, Indian State, Mallika Kaur, Punjab Police