- author: Simarjit Kaur

Every Sikh must watch City of Life and Death if they are intent on creating a unique film and memory around the Sikh genocide. This means you, a person who is a business person, doctor, taxi driver, student, poet, technologist struggling to make a living in the world, by day or night- whatever your profession, your second profession must be to educate the world about the Sikh genocide 1984-1994. Art, film, historiographies, Sikh genocide research are a part of the weaponry to combat the world of Sikh genocidal denial.

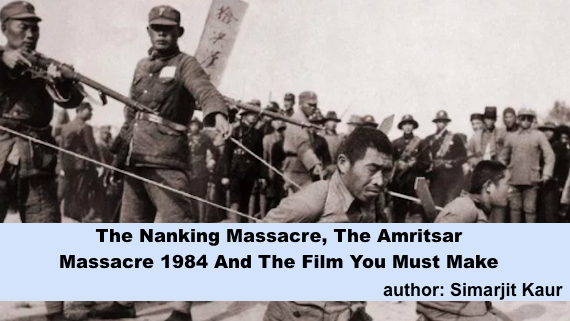

City of Life and Death is based on the Nanking massacre and was created 70 years after the event. Despite the undeniable atrocity of over 300,000 Chinese civilians brutally murdered by the invading Japanese army in 1937, revisionism of genocidal history is still continuing in Japan. Japan was a direct perpetrator and architect of appalling massacre- the ‘image’ of Japan has still glossed over the Nanking Massacre.

Revisionism in India has grown to the point that the Sikh massacre and rape of the Sikh nation is not even referred to in history books except as a flushing out of “terrorism” in Punjab. 1984 is probably not even mentioned in the average Indian history book in schools and this needs investigating. However it is worth studying further the revisionism movements across the world as part of a bigger genocide studies program.

Battle of Nanking and Nanking Massacre – Background

The Nanking Massacre was an episode of mass murder and mass rape committed by Japanese troops against the Chinese of Nanjing (Nanking)The massacre is also known as the Rape of Nanking; the Nanjing Massacre or Rape of Nanjing.

Since most Japanese military records on the killings were kept secret or destroyed shortly after the surrender of Japan in 1945, historians have been unable to accurately estimate the death toll of the massacre. The International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo estimated in 1946 that over 200,000 Chinese were killed in the incident. China’s official estimate is more than 300,000 dead based on the evaluation of the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal in 1947.

Historians estimate that between December 13, 1937, and late January 1938, Japanese forces tortured and murdered up to 300,000 Chinese (mostly civilians and surrendered soldiers) and raped tens of thousands of women during the Nanking Massacre (also known as the “Rape of Nanking”), after its fall.

In 2005, a history textbook prepared by the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform which had been approved by the government in 2001, sparked huge outcry and protests in China and Korea. It referred to the Nanjing Massacre as an “incident”, glossed over the issue of comfort women, and made only brief references to the death of Chinese soldiers and civilians in Nanjing. A copy of the 2005 version of a junior high school textbook titled New History Textbook found that that there is no mention of the “Nanjing Massacre” or the “Nanjing Incident”. Indeed, the only one sentence that referred to this event was: “they [the Japanese troops] occupied that city in December”. As of 2015, some right-wing Japanese negationists deny that the massacre occurred, and have successfully lobbied for revision and exclusion of information in Japanese schoolbooks. Denial of the massacre and revisionist accounts of the killings have become a staple of Japanese nationalism. In Japan, public opinion of the massacres varies, but few deny outright that the conflict occurred.

City of Life and Death – A Must Watch Movie

“Filming began in Tianjin in October 2007, working under a budget of 80 million yuan (US$12 million). The film endured a lengthy period undergoing analysis by Chinese censors, waiting six months for script approval, and another six months for approval of the finished film. It was finally approved for release on April 22, 2009. However, the Film Bureau did require some minor edits and cuts, including a scene of a Japanese officer beheading a prisoner, a scene of a woman being tied down prior to being raped, and an interrogation scene of a Chinese soldier and a Japanese commander.”

I found it bizarre and it definitely shifted my views on story telling as one of the Japanese perpetrators has an almost human dimension through this film despite being on the perpetrator side. I am reminded of a chance encounter when someone I came across for a few minutes told me of a relative who fought in “Operation Blue Dtar” (code-name of Indian Army’s attack on Darbar Sahib as coined by the Indian state) once I told them of my interest in survivors of 1984- an army man had been brainwashed that they were going to flush out ‘terrorists’ As soon as he entered the Darbar Sahib complex all he saw were pilgrims- unarmed civilians, women and children. I was shocked that someone could even have been fighting on the army side at that point but through his relative’s voice I briefly heard the devastation through a different angle. I have often wondered if this perspective would work in telling the story of genocide better and having seen City of Life and Death- despite it looking as if the story teller has sympathy for the perpetrator( hence all these death threats put on him and knee jerk reactions as showing the Japanese too positively)! It works in the opposite way to show the barbarity even further of the dehumanised perpetrator which is an entire system. That there are people who live, breathe, and yet are part of such dehumanisation that they are the perpetrators who do not stop the system is an area that makes a person think. Some Chinese viewers felt that the humanisation of the Japanese perpetrator side went too far. One’s first reaction is that the story is shifting in sympathy but the exact opposite happens. You wonder how someone who calls themselves a human being can carry on living and working in such genocidal acts while working on the perpetrator side. This chance story I heard- of someone’s relative fighting in June 1984 Indian army attack on Darbar Sahib ended that the man went to the USA but suffered PTSD at what had been a massacre- and his part on the perpetrator’s side and I have often wondered if this was a viewpoint I should’ve explored in my own attempts at fiction writing. City of Life and Death was successful as a film and yet created controversy upon its release in China’s mainland, as some Chinese people criticised the film’s portrayal of the Japanese soldier Kadokawa so sympathetically. The film had to be pulled from some theaters, and Lu even received online death threats to both himself and his family.’

All Sikh film makers and those who aspire to memorialise 1984 and tell the truth about the Amritsar Massacre must keep aspiring to create such unique voices. There have been brave independent attempts out of Punjab- and we shouldn’t cease in piecing the brave attempts together, even if it is years later. You, as consumers of films, Netflix, home cinemas, you tube are all potential film makers- step into this world through your own self learning, through critique and use the technology that is all pervasive, on our phones, and you can tell the world the story that must be told. First attempts maybe crude but don’t worry about the critics and instead please ensure that your alternative profession to push forward the memorialisation of the Sikh genocide continues; keep trying and you will get the audience and unique voice as Lu Chuan did.

Lu Chuan reflects on his approach to showing the perpetrator’s story in a ‘neutral’ way while telling a major story of mass rape and massacre and how this is one of the first films on the subject that tries to show atrocity through more neutral story telling and therefore brings home the horror even more. He also went through a lot of painstaking preparation and work for this film and all film makers, writers and artists should take inspiration from this.