Articles/Opinion » Selected Articles » Sikh Genocide 1984

International Law Binds Indian State To Prevent, Punish Acts of Genocide [OP-ED]

December 24, 2018 | By Upendra Baxi

by: Upendra Baxi*

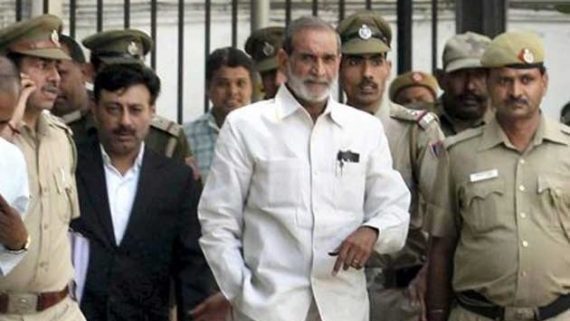

What distinguishes the learned judgment delivered by Justices S Muralidhar and Vinod Goel is not just the meticulous finding of criminality and award of punishment in the Sajjan Kumar case but the urging that “Neither ‘crimes against humanity’ nor ‘genocide’ is part of our domestic law of crime. This loophole needs to be addressed urgently.” The urgency is underscored by the observation that “2,733 Sikhs and nearly 3,350 all over the country were brutally murdered” and this “was neither the first instance of a mass crime nor, tragically, the last”.

The court refers to the “mass killings in Punjab, Delhi and elsewhere during the country’s Partition”, a “familiar pattern of mass killings in Mumbai in 1993, in Gujarat in 2002, in Kandhamal, Odisha in 2008, in Muzaffarnagar in UP in 2013, to name a few.” All these “mass crimes were the targeting of minorities and the attacks spearheaded by the dominant political actors being facilitated by the law enforcement agencies” and the “criminals responsible for the mass crimes have enjoyed political patronage and managed to evade prosecution and punishment”.

⊕ ALSO READ – DELHI HIGH COURT STOPS AT “CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY” IN CBI V SAJJAN KUMAR

Sikh Genocide 1984 instigator Sajjan Kumar.(File Photo)

These remarks are likely to be misconstrued by organised and individual political actors as judicial overreach. But they are non-adversarial in nature and scope and reflect the popular and judicial anguish at mass atrocities. The court’s suggestion for an end to impunity is meant to promote constitutional good governance. I not deal with the merits of the verdict here, but rather, with the international legal position regarding genocide.

Genocide cannot be a lone wolf crime; it has to be the work of many hands and minds working in concert and with a clear and specific intention to physically annihilate a whole group of people. Yet, howsoever much human rights activists may wish for it, cultural genocide is not yet a category of the law of genocide. Momentous, though, is the authoritative International Court of Justice ruling (in 2007) maintaining that states may also commit genocide; this is an inaugural moment in international history.

As is well known, India signed the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide on December 8, 1949 (ratified on August 27, 1959). The Convention owes a great deal to one person’s indefatigable advocacy, by Raphael Lemkin, who memorably stated that “genocide is intended to signify a coordinated plan of different actors aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves”.

Momentous, though, is the authoritative International Court of Justice ruling (in 2007) maintaining that states may also commit genocide; this is an inaugural moment in international history for it rejects Serbia’s contention that the Genocide Convention does not provide for the responsibility of states for acts of genocide. Acts of mass exodus or deportation, or measures of birth control by the state, may be regarded as genocidal acts.

The ICJ also ruled that genocide did occur in at least one instance during the Bosnian war — at Srebrenica, when some 8,000 Muslim men and boys were massacred in 1995, at the hands of the Bosnian Serb Army (VRS). The court also found “conclusive evidence” that numerous other killings and massacres of Muslims occurred in other parts of Bosnia.

But while holding that the actus reus (or “material acts perpetrated”) of genocide was established, the ICJ also controversially found that the intentional element was lacking. What distinguishes genocide, it said, from other crimes is the “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group as such” (a dolus specialis, meaning specific intent).

Mercifully, the ICJ does not merely interpret the Convention to say that states have a duty to do their best that such acts do not occur; but that in order to incur responsibility “it is enough that the State was aware or should normally have been aware, of the serious danger that acts of genocide would be committed”. John Heieck has recently argued for an implied duty to due diligence such that where necessary the five permanent members of the UN Security Council may have a duty to intervene even by military means and the rule by veto may be suspended in situations of genocide. This remains a debatable proposition; but assuredly, obligations of due diligence by the concerned state should form an integral aspect of the duty to prevent and punish.

Article V of the Convention obligates all contracting parties “to enact, in accordance with their respective constitutions, the necessary legislation to give effect to the provisions of the present Convention, and, in particular, to provide effective penalties for persons guilty of genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in article III”. And by Article 1 the “Contracting parties confirm that genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which they undertake to prevent and to punish”.

Article 51 [C] of the Indian Constitution casts a duty to “foster respect for international law and treaty obligations in the dealings of organised peoples with one another.” The duties to prevent and punish acts of genocide, reiterated by the ICJ, are binding on India, both as an aspect of conventional and customary international law; they are also an integral aspect of Article 21, the rights to life and liberty as interpreted and innovated by the apex court.

The Delhi High Court also pointedly refers to the work of the International Law Commission towards a Convention on Crimes against Humanity; its draft articles already submitted to the UN General Assembly are expected to receive governmental and non-governmental comments for likely adoption of the final text by the UN General Assembly in 2019 or 2020. “India, in view of her experience with the issue”, add their Lordships, “should be able to contribute usefully to the process”. Ethnic cleansing may not be the same, in technical law, as genocide, but the state duty to prevent and punish crimes against humanity remains as great and grave.

- The writer is professor of law, University of Warwick,and former vice chancellor of Universities of South Gujarat and Delhi.

- Note: Above write-up was originally published in The Indian Express (IE) under title: “A duty great and grave” at source url: https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/genocide-constitution-sajjan-kumar-1984-anti-sikh-riots-icj-5506492/. Its shared as above for the information of readers of the Sikh Siyasat News (SSN).

To Get Sikh Siyasat News Alerts via WhatsApp:

(1) Save Our WhatsApp Number 0091-855-606-7689 to your phone contacts; and

(2) Send us Your Name via WhatsApp. Click Here to Send WhatsApp Message Now.

Sikh Siyasat is on Telegram Now. Subscribe to our Telegram Channel

Related Topics: 1984 Sikh Genocide, 1984 Yes It’s Genocide, Genocide Prevention, Indian Politics, Indian State